Yesterday, the Hawks’ former GM Dan Ferry told the Atlanta Journal Constitution that he’s “been asking the Hawks for many months to release the results of the Taylor investigation because I wanted everyone to have those facts. For whatever reason, the team refused to release the results until after the season ended.”

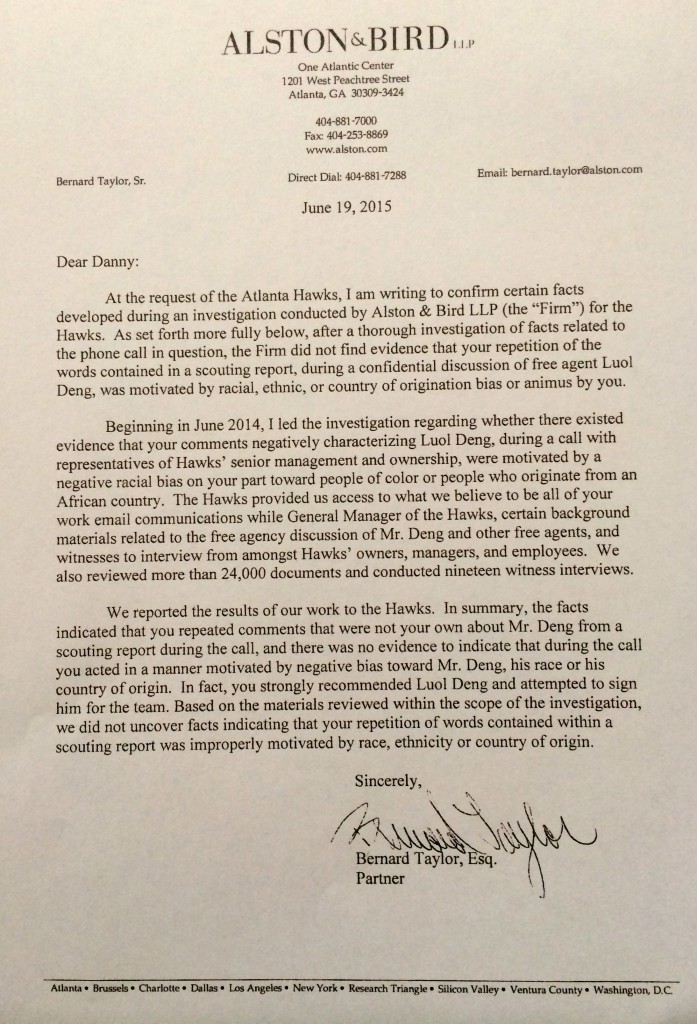

According to Ferry, the investigator had completed his investigation over 8 months ago. However, the investigator (Atlanta Attorney Bernard Taylor) only sent Ferry a summary letter advising him that the investigation did not find wrongdoing on June 19, 2015. Here’s a copy of the letter:

As a workplace investigator, that 8 month lag between September of 2014 and June 22, 2015 when they released two letters announcing the results of the investigation leaves me asking some questions.

- Why the 8 month lag?

- Why was the impartial investigator asked to draft the letter to Ferry?

- Why did the impartial investigator agree to issue the letter to Ferry?

- When the impartial investigator agreed to issue that letter to Ferry 8 months after the investigation was complete did he forget his role as neutral and move to a role of advocate?

Why the 8 month lag?

The answer to this question seems fairly obvious: The Hawks waited 8 months to share the results of the investigation publicly because they wanted to wait until the end of the basketball season. Arguably, the Hawks successfully shielded the team and franchise from media distraction and scrutiny through this delay – and the Hawks had a good run.

Why was the impartial investigator asked to draft the June 19th letter to Ferry?

This question requires a bit more reading of the tealeaves. Here’s how Atlanta employment attorney Jimmy Daniel explains it:

“The AJC has reported that on June 19, the Hawks and Mr. Ferry reached an agreement to ‘buyout’ the remainder of his contract for an undisclosed sum and on undisclosed terms.

ESPN has taken that a step further by reporting that the letter from Alston & Bird to Mr. Ferry – dated June 19 – was a condition of that settlement. I certainly cannot verify that ESPN is correct in that regard. In my experience, however, it would not be uncommon for a mid-contract executive negotiating a severance package in the context of allegations of misconduct to seek such a letter. Of course, whether he or she is successful in obtaining such a letter depends on the parties’ respective bargaining power.”

Why did the impartial investigator agree to issue the letter to Ferry?

Often employers will utilize an external investigator to review allegations of misconduct that involve senior leadership. The Hawks’ attorneys and leadership understood the value of hiring someone from the outside to investigate. With an outsider, the Hawks deflected criticism that the allegations were not properly addressed and gave them a more credible source to rely upon when it came time to make decisions based upon vetted factual findings.

What is curious with the Hawks is why the investigator wrote a letter to Ferry on June 19, 2015. While it is common for investigators to share the results of the investigation with the accused and the accuser, sometimes called a “close out” meeting, the timing – among other things – seems a bit off here.

- The “close out” letter was written months after the investigation ended.

- Ferry appears to have known the results of the investigation well before receiving the “close out” letter.

- The “close out” letter appears to assert the position of the employer, not the findings of the investigator.

When the impartial investigator agreed to issue that letter to Ferry 8 months after the investigation was complete did he forget his role as neutral and move to a role of advocate?

Put another way, this question asks whether when investigator agreed to issue the June 19, 2015 letter to Ferry over eight months after the investigation was complete he compromised his impartiality as an investigator and/or moved into a role as a representative/advocate of the employer?

Federal EEO laws require that workplace investigations into related misconduct allegations must be prompt, thorough and impartial. That means both the investigation and the investigator must be impartial and neutral. IBM, for example, learned the hard way about what happens when an investigator is not neutral.

Did the Hawks and the investigator make a similar misstep here?

In looking at the bio of the investigating attorney, Bernard Taylor, there is no question that he is a very accomplished and highly skilled advocate. According to his bio, he has over 30 years of trial experience and concentrates his practice on complex commercial litigation, products liability and pharmaceutical, environmental and toxic tort lawsuits. Additionally, he formerly conducted criminal investigations for the Detroit police force. He also has received numerous accolades for his legal advocacy.

His credentials are beyond reproach as a legal advocate. But, here’s the potential problem: Taylor wasn’t retained by the Hawks to be the team’s advocate. He was retained to be an impartial and neutral investigator.

According to the June 19th letter, Taylor’s retention was to conduct an impartial and neutral investigation into a concern that Ferry’s repetition of racially charged words in a scouting report “was motivated by racial, ethnic or country of origin bias or animus.” It appears that Taylor met this charge and delivered his report to the Hawks in September of 2014.

So, why would Taylor now – over 8 months later – write a letter to Ferry now about the investigation’s conclusions? Simply put, there does not appear to be a substantive reason for Taylor – as an investigator – to have written the letter to Ferry in June of 2015. So, again, why was Taylor the author? Perhaps, as Attorney Daniel speculated, it was part of Ferry’s contract buy out.

But, is that the role of an impartial investigator – to execute terms of a settlement? Arguably, Taylor’s conduct “served” both Ferry and the Hawks…but did it also serve the potential victims here?

As an outside attorney your actual impartiality and neutrality is imperative to the integrity of the process, but so is the perception of impartiality/neutrality. According to the Guiding Principals issued by the nonprofit the Association of Workplace Investigators:

“An outside attorney investigator conducting an impartial investigation should appreciate the distinction between the role of impartial investigator and that of advocate.”

Against these principles (and blind eye to the victims of the racially charged comments – admittedly uttered by Ferry and that originated with the Scout that he relied upon), I believe that there is a palpable argument that the investigator at least compromised the perception of his impartiality when he issued the recent letter.

Frankly, the investigator would have been better served (and the Hawks would have been better served) to have passed on the June 19, 2015 letter. Of course, this is a delicate point.

So, what do you think?

__________________________________________________________

Workplace Investigations Group offers a national directory of well-qualified attorneys who conduct impartial internal investigations. All of its workplace investigators have 10+ years of employment law experience and have agreed to support their responsibilities to the professional and impartial workplace investigations process and the parties that they serve. It also delivers training to in-house counsel, risk managers, human resources professionals and others on how to conduct internal investigations that will withstand third-party scrutiny. Click here for information on upcoming training in Washington D.C, Atlanta, and Houston.

Workplace Investigations Group offers a national directory of well-qualified attorneys who conduct impartial internal investigations. All of its workplace investigators have 10+ years of employment law experience and have agreed to support their responsibilities to the professional and impartial workplace investigations process and the parties that they serve. It also delivers training to in-house counsel, risk managers, human resources professionals and others on how to conduct internal investigations that will withstand third-party scrutiny. Click here for information on upcoming training in Washington D.C, Atlanta, and Houston.

I suppose the propriety of this would depend on who hired him to be the investigator. If the party who hired him agreed, then I suppose he could switch roles. Of course, if he obtained cooperation from witnesses on the basis of a representation of impartiality or confidentiality, I suppose the witness would have a basis for a Bar complaint, based on a misrepresentation made to an unrepresented party. If the witness suffered harm, he or she might also have a basis for a fraud claim. I can imagine other potential claims, depending on the facts.